Our ELBOW researcher Saara-Maija Kontturi spent time in Sweden for archival work during this autumn. While enjoying her time there, she wrote an archive travel log that sheds light on the everyday life of a historian and how it was like to work in the archives.

So, let Saara-Maija’s travel log with plenty of wonderful photographs lead us to Swedish archives!

Stockholm, 10 October 2025

It’s been over three weeks of an exciting hunt: tracking down the traces the Swedish medical electricity experimenters have left behind. The archive trip started with an enthusiastic note, as the first days in Uppsala revealed a delightfully abundant offering of academic dissertations concerning the use of electricity in medicine, most of them in Latin, but also a few in Swedish.

The dissertations are accessible in a special reading room in Carolina Rediviva, the old library of the University of Uppsala. The library also presents a free exhibition on the library’s collections from the past 400 years. Both the cathedral and the Uppsala castle are close to the library, along with Gustavianum and its famous anatomical theatre (Gustavianum and the Uppsala Cathedral in the photo on the left). This time I did not visit the theatre as I had seen it before, but it is a very special detail in Uppsala’s medical and scientific history.

The most surprising finding in Carolina Rediviva was a dissertation on medical electricity made by a Finnish physician. William Nylander conducted the study “Några iakttagelser vid Inductions Electricitetens Therapeutiska användning” under the surveillance of medical professor, assessor Immanuel Ilmoni and it was published in 1847 in Helsinki. This is especially interesting because I had assumed there might not have been any remarkable experiments or studies with medical electricity in Finland before the late 19th century, or if there had been, accounts of them might not have been preserved. I was happy to be wrong in this case. The second interesting aspect is that Finland had not been part of Sweden for almost four decades by 1847, but the Swedish heritage of medicine was still strong in Finland, preserving ties to Swedish universities.

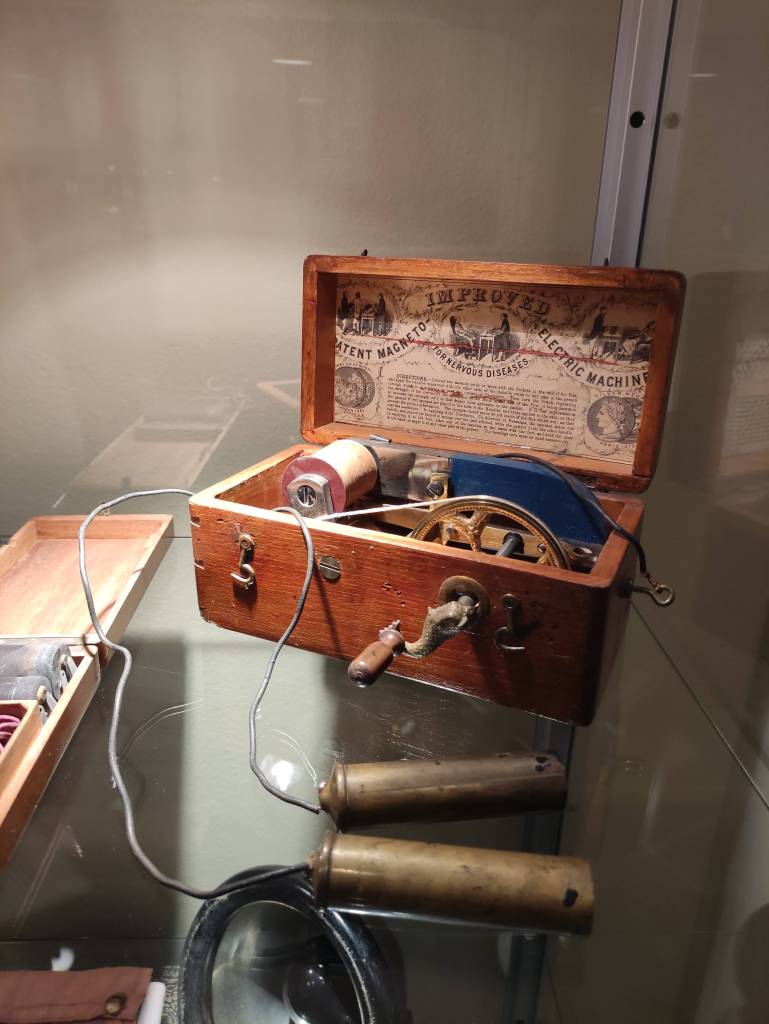

After the main serving in the library, Uppsala offered yet another treat for a medical history researcher: Medicinhistoriska Museet, the Medical History Museum (the photo on the right). Showcasing over 300 years of history of medicine, the museum holds an impressive collection of medical machines, tools, equipment, and documents. The main attraction for me in the museum was, of course, the electrotherapy machine and the related equipment, as you can see from the photos below, together with a bust of Olof af Acrel.

After nearly two weeks in Uppsala, it was time to move on to Stockholm. The Academy protocols revealed that Swedish count Carl Johan Cronstedt donated an electric machine to the Academy in 1747. After that, the machine was used by several scientists and physicians within the Academy until the middle of the 1750s. The early phase of medical electricity in Sweden was thus closely tied to the activity in the Academy and most of the publications were published by the Academy’s Handlingar. The enthusiasm waned somewhat following the initial surge, but the topic was revisited by several scholars from the late 18th to the first half of the 19th century, both within the Academy and in the University of Uppsala.

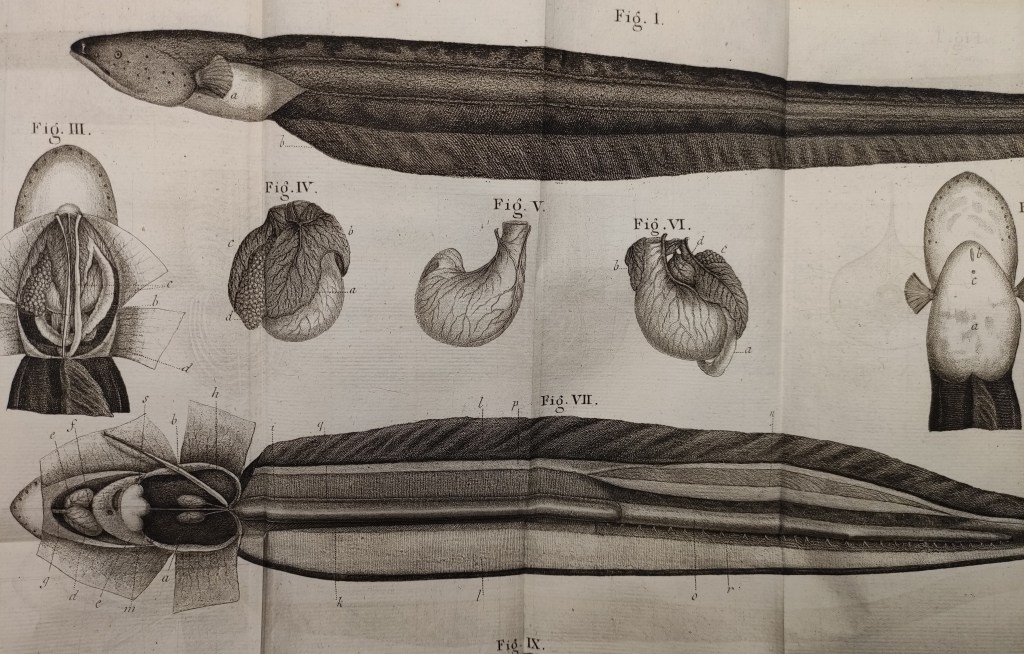

In the Academy, the most interesting materials were Gustaf Fredrik Hjortberg’s extensive diary on his electrical experiments from 1765 (the photo on the left), and Samuel Fahlberg’s detailed description of electric eels and galvanism in the remote Swedish Caribbean colony of St. Barthélemy, 1801. I got to do some exciting detective work with the connections between the experimenters and scientists who wrote about electricity – most of them seemed to know each other and worked in close collaboration in the Academy.

Fahlberg was an exception in the sense that he operated in a whole different location, far in the Caribbean island. Fahlberg was accomplished not only as a physician and natural philosopher, but also as a drawer depicting the local flora and fauna and mapping the island. His publication (1801) on eels ends with an elaborate drawing of the electric eels’ anatomy (the photo on the right).

During the past weeks, there has been a lot of joy of discovery. With some archive visits, one just comes to get access to what they already know is there; with some visits, one goes to check what is available and may even leave with empty hands. This time I knew I would find some correspondence from certain practitioners and maybe a few publications, but didn’t know if I’d get much else. My expectations were exceeded with both the quantity and quality of the material. Our project’s new research assistant Sigrid Autio has already helped a lot with the initial analysis of the materials, and I will soon start unpacking them when I get back to Finland.

Speaking of research assistants, two other special feline assistants were hired along for the trip. Their main tasks were dragging the researcher in charge outside for walks every once in a while and making sure that the butt-warming machine, I mean, the computer stays on and warm at all times. They tried writing, too, but we concluded that fingers are more optimized for that job than paws.

More about the findings in Sweden in the upcoming ELBOW Talk on 18th November!

Author & Photos

Saara-Maija Kontturi

Jätä kommentti