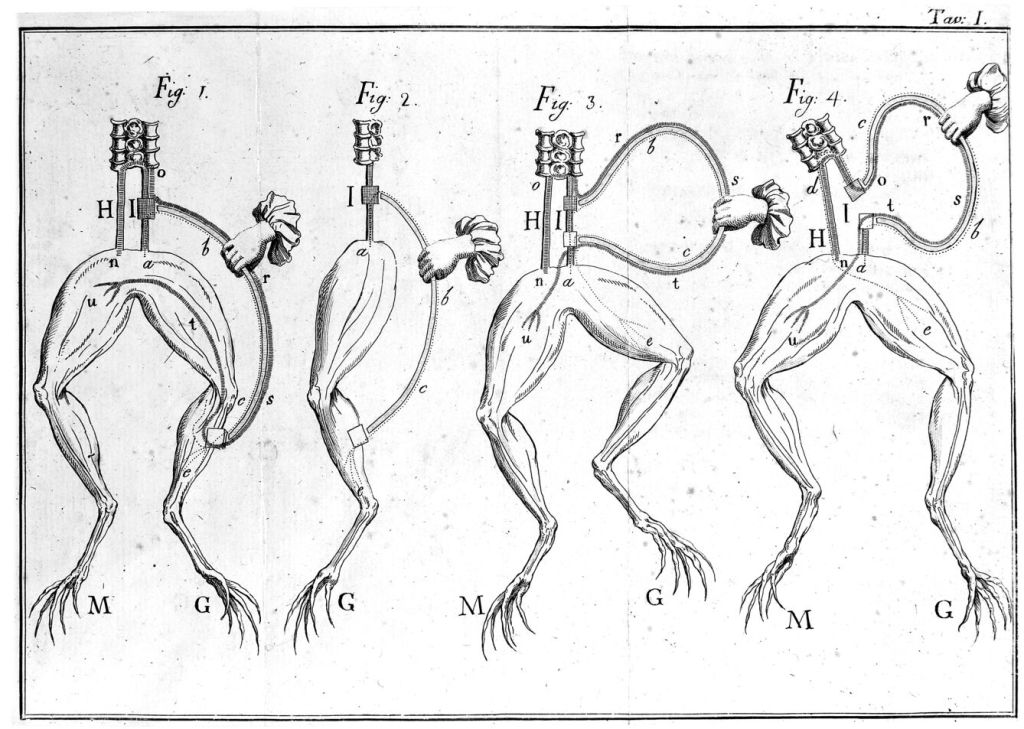

It all started with frog legs, namely the frog legs being tested upon by the Italian physician Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) in Bologna. Galvani discovered what he called “animal electricity” by showing that frog legs would move and their muscles contract when the nerves in the legs were exposed to zinc and copper rods.

Many ideas and theories around the vital force and healing properties of electricity had already been floating around for decades, and Galvani’s experiments seemed to confirm that electricity was somehow present in all animals, humans included. But it was Galvani’s nephew, Giovanni Aldini, who would take these ideas on a whole new, spooky level.

In this essay, we are having a Halloween-inspired look on the history of electricity. What were the material-cultural consequences of experimenting the connection between electricity and bodies?

Gruesome experiments on human bodies

As a young aspiring physicist, Aldini worked as his uncle’s assistant and was fascinated by his experiments on frogs and animal electricity. Particularly after Galvani’s theory was disputed by another famous Italian physicist, Alessandro Volta, Aldini became increasingly devoted to take animal electricity further and demonstrate and defend his uncles’ ideas in an even more gruesome form.

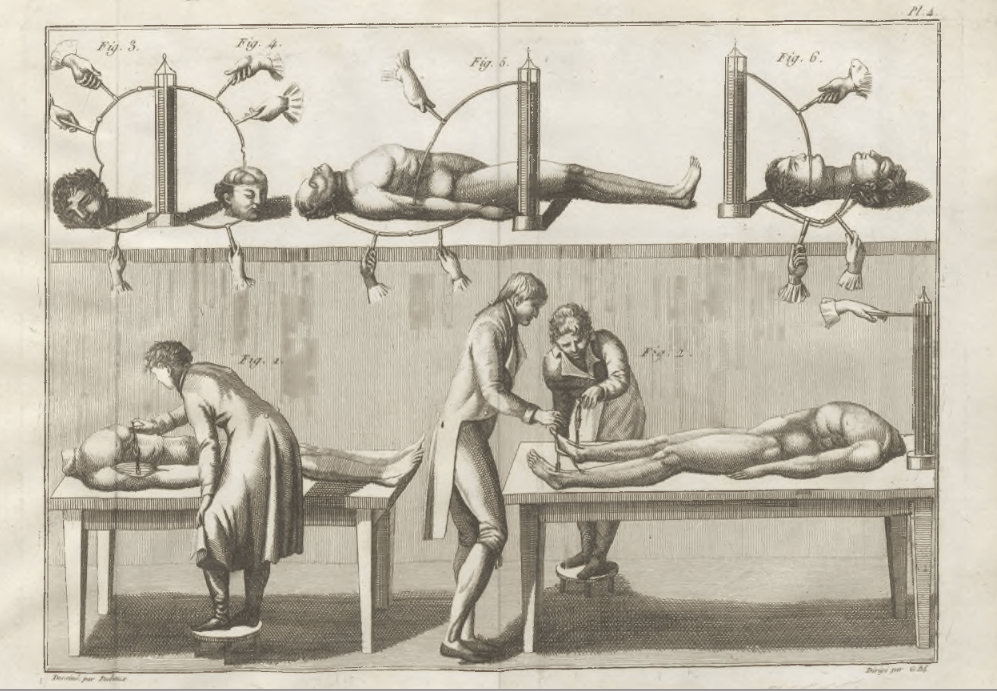

Aldini travelled around European Universities, demonstrating the power of animal electricity by shocking the bodies of recently executed criminals. Back in Bologna in 1802, Aldini experimented on two bodies that had been decapitated only a few hours prior to his experiments.

Source: Wellcome Collection.

To a shocked audience, he showed how even after death the faces of the decapitated heads could still be made to make grimaces, produce saliva and move in a variety of ways. Aldini even removed a part of the cranium of the decapitated head and experimented on shocking the brain with electricity, resulting in “strong convulsions of the face”. He also experimented on the body, making the limbs move and contract, as well. He even amputated a leg of one of the criminals, to experiment on electricity’s effect on a lone limb.

A year later in 1803 in London, Aldini was able to experiment on a dead body that was fully intact. A convicted murderer by the name of George Foster, had been hanged only hours before Aldini conducted experiments on his dead body. Aldini experimented on the body for over seven hours and made its limbs move and face animate, as the following quotation describes:

”The bodies of human corpses became violently agitated and one raised itself as if about to walk; arms alternately rose and fell; and one forearm was made to hold a weight of several pounds, while the fists clenched and beat violently the table upon which the body lay. Natural respiration was also artificially reestablished and, through pressure exerted against the ribs, a lighted candle paced before the mouth was several times extinguished.”

– Paul Fleury Mottelay, in his Bibliographical History of Electricity and Magnetism (London: C. Griffins & Col, Lts., 1922)

Aldini claimed he was not attempting to reanimate the body fully, but some members of the audience were at least intrigued by how close Aldini seemed to come in such an attempt, by making the arms of the body rise on their own and so on.

Aldini’s experiments were gruesome and even grotesque, but his reasoning behind the necessity of these experiments seems to have always been scientific. Aldini, convinced by the fact that animals possess some vital force in the form of electricity, wanted to find out how long and in what capacity the human body retains said vital force.

To find the answer to this question, the most natural route was to experiment on dead bodies. Of course, as we now know today, and as Volta had already suggested in the late 1790s, these tests did not show how much the bodies themselves held electricity, but instead how well they conducted it.

The fascinating interplay of life and death

In the 18th century, medical electricity emerged as a controversial yet intriguing practice. Practitioners believed that electrical currents could cure various ailments, from paralysis to mental disorders. This fascination, however, was often tinged with morbid curiosity, as demonstrations frequently showcased the dramatic effects of electricity on the human body.

Patients were subjected to shocking treatments that sometimes resulted in convulsions, causing onlookers to marvel at the spectacle of suffering. The interplay of life and death loomed large; the electrical experiments echoed the era’s broader themes of mortality and the limits of human understanding. Surgeons and physicians often used corpses in their demonstrations, highlighting the grim reality of medicine’s experimental nature.

As the public flocked to these displays, a macabre fascination with the ”electrical cure” reflected deeper anxieties about health and the body, revealing a complex relationship between hope, fear, and the uncharted territories of medical science.

Galvani’s frog experiments and Aldini’s tests on decapitated heads suggested a connection between electricity and muscle contraction, challenging traditional views of physiology. This interplay between life and electricity not only captivated the scientific community but also sparked debates about the nature of life itself, intertwining themes of vitality, death, and the mysteries of the living organism.

Early experiments aimed at reviving the dead using electricity were steeped in a mix of scientific ambition and macabre fascination. Following Galvani’s revelations about bioelectricity, researchers began to experiment with electrical currents on recently deceased bodies, believing that electrical stimulation could somehow reanimate them.

Aldini’s cadaver experiments not only drew crowds eager for a glimpse of the miraculous but also stirred philosophical debates about the boundary between life and death. The spectacle of ”resurrection” through electricity captivated both the scientific community and the public, revealing deep-seated anxieties about mortality and the possibilities of manipulating life itself, even as these attempts often ended in failure and horror.

Body snatching as a business

The electrical experiments required bodies, and especially in England, there was an increasing demand and decreasing supply of legally obtainable bodies for medical experiments. The most prevalent need was for dissections to be performed by medical students.

At the same time, the act of opening a human body was still condemned. The 1751 Murder Act in England set up public dissections as an additional punishment for murderers, as only the deterrent of death penalty didn’t seem to be enough, and dissection was seen as a suitable post mortem fate only for executed criminals.

As there was both a requirement for more dissections during the medical studies as well as an exponentially growing number of students from the late 18th to the early 19th century, the number of legally obtained bodies of convicted murderers was simply not sufficient for the growing demand.

According to the English law of the time, stealing a coffin was a punishable crime, yet stealing a body was not, despite being morally and religiously condemnable. As it was said, “the first grave robbers were gentlemen”, medical students and their professors themselves. Later, a whole dark market of professional grave robbers was established.

Source: Wellcome Collection.

As a business, body snatching was rather well paying but dangerous and difficult, as the bodies needed to be dug up in secret before they decomposed. This eventually led to specifically murdering people for the sake of selling their bodies for medicine. The most famous of such murderers were William Burke and William Hare, who murdered 16 people during 1827 and 1828 until they were caught – coincidentally, on Halloween, 31 October 1828.

The escalating problem of body snatching and its related criminal acts, as well as the subsequently deteriorating reputation of medical students and professionals – seen in, for example, how some believed the cholera epidemics of the 19th century were set up by medical professionals just to get more bodies for medical purposes – led to riots and eventually legal actions against body snatching.

The 1832 Anatomy Act made grave robbing illegal and aspired to get more legal bodies available for medicine. Eventually, embalming became common practice in the late 19th century, offering a better preservation and a steadier supply of bodies for medical needs.

Electricity, popular culture, and Frankenstein

With the emergence of “fashion-science” electricity in the 18th and early 19th century, the influence of electrical phenomena on culture and even literature grew stronger. Within the novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, Mary Shelley involved electricity and the interplay of life and death in the famous story of Frankenstein.

Inspired by galvanism, she explored the idea of a creature made from inanimate matter that is brought to life in her story, originally published anonymously in 1818.

The exact method is not explained, but its creator, Victor Frankenstein, resembles the electricians of the 18th century who – sometimes recklessly – pursued various experiments to explore the origins and potential uses of electricity. Of grotesque proportions and gruesome appearance, the creature is an unknowing being thrust into a world that is hostile to it.

The story takes a tragic twist when the monster starts kill Frankenstein’s loved ones, including his wife on the night of their wedding and Frankenstein starts a futile hunt to destroy what he created.

The novel, published in a revised version in 1831, became quite popular. The horrid appearance of the creature was famously shaped by Boris Karloff’s performance in the horror movie Bride of Frankenstein from 1935. It is only in this film that the vitalization of the creature is portrayed as a result of electricity in a clearer way.

This depiction significantly influenced the cultural image of Frankenstein’s creature (sometimes referred to as Frankenstein itself) as a symbol of monstrosity and inspired numerous films, TV series, theatre productions, and works of literature.

Happy Halloween!

Authors

Associate Professor Soile Ylivuori

University Researcher Stefan Schröder

Postdoctoral Researcher Saara-Maija Kontturi

Doctoral Researcher Edna Huotari

References

Aldini, Giovanni: Essai théorique et expérimental sur le Galvanisme avec une série d’expériences. Imprimerie de Fournier fils, 1804.

Aldini, John:”An account of the late improvements in galvanism”. Scientific and Medical Knowledge Production, 1796-1918. Routledge, pp. 70–75. 2023.

Frank, Julia Bess: “Body Snatching: A Grave Medical Problem”. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, Vol. 49, pp. 399-410, 1976.

Gaderer, Rupert: ”Liebe im Zeitalter der Elektrizität. E. T. A. Hoffmanns homines electrificati”. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft, Vol. 18, pp. 43–61, 2007.

Heering, Peter: ”Batterien aufladen und andere Metaphern in und aus der Elektrizitätslehre: Einige Anmerkungen”. Metaphorik.de, Vol. 26, pp. 39-59, 2016.

Hochadel, Oliver: Öffentliche Wissenschaft. Elektrizität in der deutschen Aufklärung. Göttingen 2003.

López-Valdés, Julio César: ”From Romanticism and fiction to reality: Dippel, Galvani, Aldini and “the Modern Prometheus”. Brief history of nervous impulse”. Gac Med Mex, Vol. 154, pp. 83-87, 2018.

MacDonald, Helen: Legal Bodies: Dissecting Murderers at the Royal College of Surgeons, London, 1800-1832. Traffic, 2003.

Mitchell, Piers (ed.): Anatomical Dissection in Enlightenment England and Beyond: autopsy, pathology and display. Ashgate Publishing Company. 2012.

Olry, Regis: ”Body Snatchers: the Hidden Side of the History of Anatomy”. The Journal of Plastination, October 25, 2024.

Ross, Ian & Urquhart Ross, Carol: “Body Snatching in Nineteenth Century Britain: From Exhumation to Murder”. British Journal of Law and Society 6, no. 1, pp. 108–18, 1979.

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft: Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus. Edited with an introduction and notes by M. K. Joseph. Oxford 2008.

Jätä kommentti